17th March 2019

[Is stress the most important cause of cardiovascular disease?]

Forgetting for a moment attacks by various people, and newspapers, that shalI remain nameless [Mail on Sunday UK], I thought I would return to the more interesting topic of what actually does cause cardiovascular disease and. As I have done several times before, I am looking at stress/strain.

I know that, deep down, most people feel that stress can lead to illness. ‘Oh, I was terribly stressed, then I went down with the flu.’ Or ‘He has been under a lot of stress and had a heart attack.’ If we go back over a hundred years William Osler, a famous physician, described a man suffering from angina as ” … robust, the vigorous in mind and body, the keen and ambitious man, the indicator of whose engines are always at ‘full speed ahead’ “.

The idea that hard driving Type A personalities were more likely to die of heart attacks gained great popularity at one time. But you don’t hear so much about this anymore. It is all diet, and cholesterol, and blood pressure and diabetes and tablet after tablet. Measure this, monitor that, lower this and that.

I believe that the side-lining of stress to be a monumental mistake. Because it remains true that stress is the single most important cause of heart disease, and I intend to try and explain exactly how this can be. Once more into the breach dear friend.

I shall start this little journey by explaining that stress is the wrong word to use. In fact, the use of the word stress has often been more of a barrier than an aid understanding. This is because, when we talk about stress, we really mean strain.

Stress or strain

It was Hans Seyle who coined the term ‘stress’ to cover the concept of negative psychological events leading to diseases, specifically heart disease. Of course, this is a terrible oversimplification, but it will do for now. Seyle later admitted that, had English been his first language (he was born in Slovakia) he would have used the term strain, not stress.

This is because stress is the external force placed on an object, or a human being. Strain is the resulting deformation or damage that can occur. Therefore, it is the resultant strain that is the driver of ill health.

For example, being told you are a useless idiot by one or another parent would be considered a significant external negative ‘stressor.’ The resultant anxiety and upset then represents the strain. However, the two things do not necessarily match up very well.

If you are highly resilient, or perhaps deaf, being told you are a useless idiot may have absolutely no effect on you whatsoever. You will continue to whistle a happy tune, whilst skipping along the pavement.

If, on the other hand, you are a rather more sensitive soul, or perhaps being told you are a useless idiot is a daily occurrence, then the resultant strain/deformation may be quite severe. In this case, the same external stressor can result in completely different levels of internal strain – depending on the resilience of the individual.

To give another example, some people enjoy giving public talks, they look forward to it. Others would rather chew their own arm off rather than stand up and talk in public. Once again, we have the same external stressor, resulting in completely different levels of internal strain.

The death of a close relative, such as a husband, is a major negative stressor which, for most people would cause a significant burden of strain. However, if the husband was an abusive bully, who regularly beat his wife, the death may be a blessed relief and the levels of strain will be reduced greatly. Then again, the conflicting feelings of guilt, relief, happiness and grief can lead to immense strain.

In short, there is no point in saying that an individual is under a great deal of stress. That may or may not be true, but it is very difficult to define, or measure. What matters is their response to negative stressors – real or perceived. The internal strain.

Of course, this does not mean that you can discount external stressors. These can be very important on both an individual, and a population wide basis. So, before looking at strain in more detail, I am going to review external ‘population-wide stress(ors)’.

Population-wide stressors

Whilst this is a fascinating area, the terminology used is more than a little variable, and confusing. One of the problems is that the terminology swirls around, and people write about the same thing using different words or use the same words to describe different things. A bit like using IHD, CHD, CAD and CVD to describe much the same thing, I suppose.

To keep this simple, and stripping terminology down things down to basics, the concept I am trying to capture, and the word that I am going to use, here to describe the factor that can affect entire populations is ‘psychosocial stress’. By which I mean an environment where there is breakdown of community and support structures, often poverty, with physical threats and suchlike. A place where you would not really want to walk down the road unaccompanied.

This can be a zip code in the US, known as postcode in the UK. It can be a bigger physical area than that, such as a county, a town, or whole community – which could be split across different parts of a country. Such as native Americans living in areas that are called reservations.

On the largest scale it is fully possible for many countries to suffer from major psychosocial stress at the same time. This happened very dramatically after the breakup of the Soviet Union, which started in some countries earlier than others e.g. Poland. But the main event was the fall of the Berlin wall, and the collapse of communism across most of Eastern Europe. It was studied quite closely by a number of researchers. Here is one paper:

‘The mortality crisis in transition economies. Social disruption, acute psychosocial stress, and excessive alcohol consumption raise mortality rates during transition to a market economy.’ 1

As the paper states:

‘Acute psychosocial stress was one of the main drivers of the sharp mortality increase experienced by the former communist countries of Europe. In central Europe, the post-communist mortality crisis was quickly solved, while in much of the former USSR, life expectancy at birth did not return to 1989 levels until 2013.’

The splintering of the Soviet Union is something to be, generally, celebrated. However, it caused a massive surge in premature deaths, mainly from cardiovascular disease (CVD).

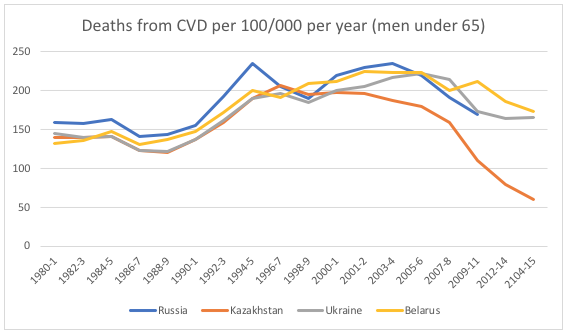

Below is a graph which tracks at CVD deaths in men under 65s in four former Soviet countries: Russia, Kazakhstan, Ukraine and Belarus. The graph starts in the year 1980 and goes on to 2015 2.

CVD was similar in all four countries and was pretty steady, perhaps gently falling. Then, Berlin wall fell in 1989, with major disruption hitting Russia by 1991 when Gorbachev was ousted by Yeltsin. At which point CVD took off in all country.

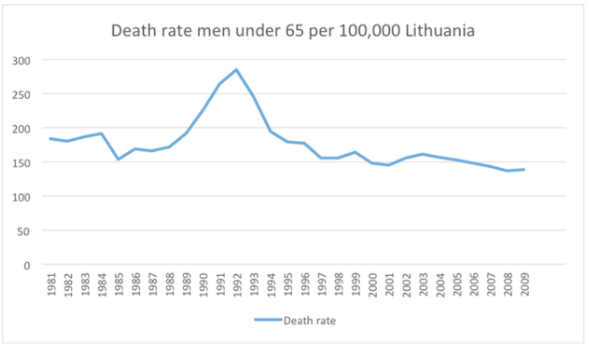

It may be easier to see a clear pattern if we look at a single country in the Soviet Union, Lithuania. This is a graph that I have used several times before. Figures are from Euro Heart Statistics.

In Lithuania CVD was gently dropping until 1989 then – Bam! Virtually a doubling of the rate in a five-year period. Then it dropped straight back down again.

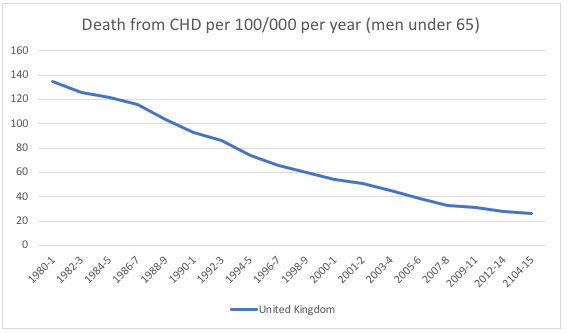

If you want a comparator country in Europe, here is the UK during the same time period. A steady uninterrupted fall (completley undisturbed by the launch of statins in 1987) Every other country in Western Europe, the USA, Canada, Australia etc. show the same pattern as the UK – a steady fall.

Getting back to the Soviet Union, it is it interesting that the main increase in those who died was seen in men, mainly middle aged men. To quote from the social disruption paper again:

‘Looking back, it could have been expected that the European mortality crisis would primarily have affected children, pregnant women, the elderly, and the disabled. Yet, as shown.. men were much more affected than women in every transition country. The fastest relative upswing in mortality was recorded for 20−39 year olds, who experienced a marked rise in violent deaths, while the fastest absolute rise occurred among 40−59 year olds, who were mainly affected by a rise in cardiovascular deaths.’

It seems inarguable that extreme psychosocial stress, as experienced in ex-Soviet Union countries after 1989, drove a massive spike in CVD deaths, which is only now beginning to settle down in many of the countries.

As an important aside, you may notice that, in Russia, the rate of CVD rose quickly from 1990 until about 1995, then dropped. Then it jumped up again in 1998. You may ask, what happened in 1998? Well, this was the year of the collapse of the Ruble – known as the Ruble crisis. It resulted in massive financial chaos, and levels of poverty exploded.

‘Mobs trying to get their savings were barred from entering the banks, executives flew to London to get suitcases full of dollars and coup plans were discussed in the newspapers. The value of the stock market dropped to 10 percent of its value of the previous year, the value of Ruble tumbled by 75 percent, and 18 of Russia’s 20 major banks effectively collapsed under massive debts. Foreign investors, some of them calling Russia “Indonesia with nukes,” fled the country.

Some have said the damage to the economy was greater than that unleashed by Hitler’s armies in World War II. By the time of the 1998 Ruble crash ran its course the poverty level had increased from 2 percent of the population in the Soviet era to 40 percent.’ 3

Moving away from the Soviet Union to the population that has undergone the single greatest and most extreme form of social breakdown and disruption, social stress and dislocation known. This is the Australian aboriginals. A group of people that has been subjected to an immense burden of negative stressors.

Here are a few bullet points from a study carried out by the Australian Government:

- Stress is a significant factor of the lives of Aboriginal young people.

- High levels of self-harming intent and behaviour. Feelings connected to loss of hope – high levels of anxiety and depression

- Rapid social change in Aboriginal communities.

- Interpersonal violence, accidents and poisoning, stress, alcohol and norms of violence as in male to male fighting.

- Domestic violence and child abuse, as well as sexual assault, are further stressors and sources of mental ill health.

- These behavioural outcomes reflect the impact of historical factors, colonisation and disadvantage.

What impact has this had, specifically on cardiovascular disease rates? A research study was done, called the Perth Aboriginal Atherosclerosis Risk Study (PAARS) population. The investigators looked at CHD (coronary heart disease), not CVD (cardiovascular disease) – which would also include strokes. Sorry for jumping about in the terminology, but everyone does. Indeed, it is hard to find two studies that use the same terminology, or end points.

Sticking to CHD, which basically means deaths from heart attacks, researchers found that the CHD rate in Austrailian Aboriginals was 14.9 per 1000/year versus 2.4 for the general population. This is 1,490 per 100,000 per year [this is metric most commonly used] and represents the highest rate I have ever seen in any population, in any country, at any time – ever. Although Belarus came pretty close at one point.

What also stands out is that the rate of heart attacks in Aborignal Australians was six fold higher than the surrounding population. However, if we separate the figures from men and woman, we can see something even more astonishing.

For Aboriginal men the rate of CHD was 15.0 versus 3.8 per 1000 per year. A four hundred per cent increase on men in the surrounding population. For aboriginal women the CHD was almost exactly the same as for the men, 15.0 per 1000 per year – which is highly unusual in itself – as men normally have a much higher rate than women.

The astonishing fact is that Australian Aboriginal women had a rate of CHD that was ten times the rate of the surrounding female population. Or, to put it another way. One thousand per cent higher. 4

A similar picture, though less extreme, can be seen in Native Americans. As outlined in this 2005 paper. ‘Stress, Trauma, and Coronary Heart Disease Among Native Americans.’ 5

‘This study quantified exposure to trauma among American Indians, adding to the existing evidence that this population experiences a disproportional amount of trauma. We were intrigued by the statement “It may be that high rates of trauma exposure contribute to the increasing prevalence of cardiovascular disease among American Indian men and women, the leading cause of death among this population” and wanted to lend support to this assertion. Indeed, American Indians now have the highest rates of cardiovascular disease in the United States.

In a study similar to the AI-SUPERPFP study (American Indian Service Utilization, Psychiatric Epidemiology, Risk and Protective Factors Project (AI-SUPERPFP) Team). Koss et al. documented adverse childhood exposures among 7 Native American tribes and compared these exposures to levels observed in the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study conducted by Kaiser Permanente and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in a health maintenance organization population. Compared with participants in the ACE study, not only did the American Indians have a significantly higher rate of exposure to any trauma (86% vs 52%), but they also had a more than 5-fold risk of having been exposed to 4 or more categories of adverse childhood experiences (33% vs 6.2%).’

Wherever you look, you can see that populations that have been exposed to significant social dislocation, and major psychosocial stressors, have extremely high rate of coronary heart disease/cardiovascular disease.

This can be supported if we look at the twenty countries in the world that have the highest rates of CVD – both men and women. Figures from WHO 2017 6. Ex-soviet countries in bold

- Turkmenistan

- Ukraine

- Kyrgyzstan

- Belarus

- Uzbekistan

- Moldova

- Yemen

- Azerbaijan

- Russia

- Tajikistan

- Afghanistan

- Syria

- Pakistan

- Mongolia

- Lithuania

- Georgia

- Sudan

- Egypt

- Iraq

- Lebanon

I feel that some of these figures may not be entirely accurate. Such as the CVD rate in Syria, or Iraq in the last few years. As for the rest. I would not like to comment on the social and political situations in all of these countries in too much detail. However, we are not looking at peaceful and mature democracies here. Mainly dictatorships and countries riven by internal conflict.

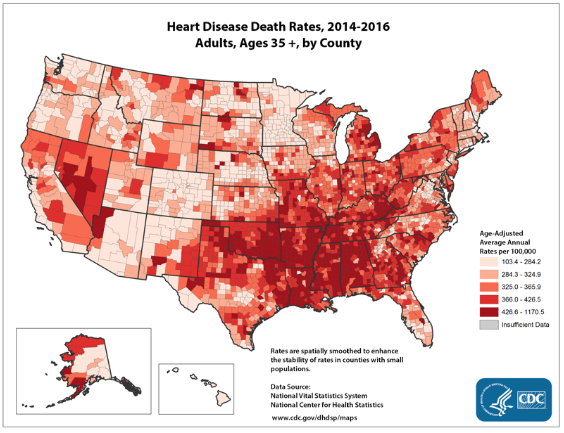

Winding this back to the US, there is a pattern of CHD showing that certain counties suffer much higher rates than others. Figures taken from the CDC. On this graph darker means a higher rate of heart disease, lighter means less heart disease. These are deaths per 100,000 per year. You may discern a pattern.

The UK shows precisely the same sort of picture with inner cities and more deprived areas, having much higer rates than affluent suburbs.

Wherever and however you look it becomes apparent that higher levels of psychosocial stress are strongly associated with CVD/CHD. In some cases, very strongly indeed.

But how can psychosocial stress and factors such as childhood trauma, as seen in the Australian Aboriginals, or Native Americans, lead to a build up of atherosclerotic plaques in the arteries,the main cause of CVD?

Or to put it another way, how does a negative external stressor, lead to the internal physiological strain, that causes CVD? For that we need to turn to Sapolski, Bjortorp and Marmot. Which comes next!

1: https://wol.iza.org/uploads/articles/298/pdfs/mortality-crisis-in-transition-economies.pdf

3: http://factsanddetails.com/russia/Economics_Business_Agriculture/sub9_7b/entry-5170.html