My son tends to dismiss the idea of watching any film from before about say, the year 1990. Terrible special effects, he informs me, and just too old. As for anything in black and white … no, just, no. Why watch old stuff, it’s rubbish. The fool.

In science there also seems to be a tendency to think that things are constantly moving forward, building on what has gone before. Old research and ideas, become obsolete, and fade from memory. There is no need to look back. We can learn little, or nothing, from things we did a hundred or more years ago.

True? Let me take you back to a land that seems far away and long, long ago. A place where the sun was used as a powerful ‘medicine’. Patients with tuberculosis (TB), or those with non-healing wounds, or mental illness, and many other things. They were wheeled into solariums to make the most of the sun’s rays. Many hospitals had great big windows to let in sunlight.

Years ago I read a fascinating book on this called ‘The healing sun’ which looked at how the sun was used to treat many illnesses. Often with impressive results. It certainly awakened my interest in the area. And, because I have an obsessive interest in heart disease, I focussed on nitric oxide (NO), which is synthesised when the skin is exposed to the sun. [This is not the only way NO is created in the body, but it is important].

Nitric oxide is a molecule that is now understood to be critical for cardiovascular health, although it was not known to have any role a hundred years ago. Until recently it was not known to exist inside the body. in fact, the idea that such a highly reactive compound could have a positive role to play was considered bonkers. Super-reactive – and damaging.

I would like to point out that sunlight does many more things than create nitric oxide and, of course, vitamin D. Mostly good. With so many potential benefits why did the era of ‘solar treatment’ fade into darkness? I think it is almost entirely due to the arrival of antibiotics. A whole bunch of terrible infections, which killed so many millions became treatable – virtually overnight. Sunlight was no longer required, or so it appeared. We had a new solution. Faster, and more effective.

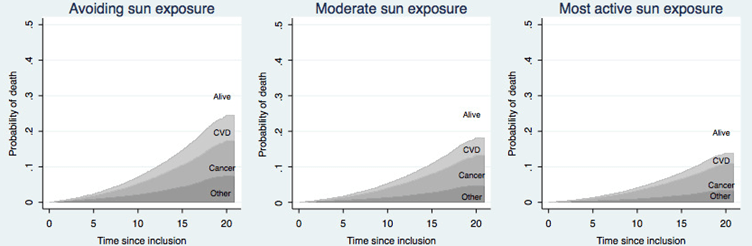

And then came the slow, but inexorable, one-hundred-and-eighty-degree turn. The sun began to be viewed as dangerous. From ‘healing sun’ to ‘bringer of death’. Has this been a good move? In my opinion, absolutely not. Let me show you a graph from a long-term study done in Sweden. It looks at probability of death, in three groups.

- Those who avoid sun exposure.

- Those with moderate sun exposure.

- Those who actively sought out the sun1.

Over a twenty-year time period, those who actively sought the sun were ten per cent less likely to die – of anything, than those who avoided it. This was an absolute, not a relative risk.

On the basis of this study, sunlight would be considered a miracle drug. Everyone in the world urged to take it, every day, without fail. The pharmaceutical company with a patent for any such medicine would become rich beyond the wildest dreams of avarice. You would never hear the last of it.

I make this somewhat bold statement because there is no medication, nothing else at all, that comes close to this level of overall health benefit, and life extension. Nothing … at all. Stopping smoking would be almost as good, providing about eight to ten years of added life. But that is not really the same thing.

That paper was published ten years ago. A more recent one, from 2020, had pretty much exactly the same thing to say about sunlight. The title says it all, really:

‘Insufficient Sun Exposure Has Become a Real Public Health Problem.’

‘This article aims to alert the medical community and public health authorities to accumulating evidence on health benefits from sun exposure, which suggests that insufficient sun exposure is a significant public health problem.

Studies in the past decade indicate that insufficient sun exposure may be responsible for 340,000 deaths in the United States and 480,000 deaths in Europe per year, and an increased incidence of breast cancer, colorectal cancer, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, autism, asthma, type 1 diabetes and myopia.’ 2

Eight hundred and twenty thousand deaths a year … seems a lot. Their figures, not mine.

My own view is that the big bright thing up in the sky … Well, it has been shining down on all life forms – all of them on land at least – for five hundred million years – give or take. And for most of our existence, humans have spent the majority of daylight hours outside. Thus, from an evolutionary perspective, it is probably not a great idea to avoid the ‘giver of life’, as I now like to call it. We may be missing out on something, or several somethings, which are rather important.

Over the years, there have been many studies demonstrating that sun exposure is really important for our health and wellbeing. But none of them had the slightest effect … on anything. Instead, we are increasingly told to cower away in terror. In Australia, land of ‘slip slap and slop’, they are now creating massive sunshades around schools, so that children who dare to go outside and play will be protected from the sun at all times. Hoorah. Good job.

My previous blog was about disruptive science. An area where there has been a drastic contraction over the last fifty years. Why? Well, one of the main reasons is that disruptive science seems to have little, to no, effect. ‘My mind is made up, do not confuse me with the facts.’ Why bother going against the mainstream view when it achieves the square root of bugger all.

The mainstream view in this area is that sun exposure causes skin cancer. Which means that any discussion on potential benefit is shut down immediately. Yes, there is some robust research to show that fair skinned people, living in hot and sunny lands, are more likely to develop skin cancer.

However, the evidence that there is an increased risk from malignant melanoma is far from clear. There are many different forms of skin ‘cancer(s)’, and most are very easily spotted and easily treatable, and removed. Whilst unpleasant, most of these are not remotely life threatening.

Australia has been banging the ‘anti-sun’ drum for decades. To great effect?

- In 1982, 596 people died of malignant melanoma.

- In 2023 1,527 people died of malignant melanoma

That represents a 2.6-fold increase. In case you were wondering.

The population of Australia went up by 1.8-fold during the same time period. Although I am informed by Google AI that ‘The age-standardised mortality rate for malignant melanoma in Australia has generally remained stable or decreased over the last twenty years.’ You think?

I think 2.6 is a bigger number than 1.8. Thirty per-cent bigger. Yes, I know you can play statistical games to create ‘age-standardized’ rates, whereby 1.8 becomes a larger number than 2.6. ‘Bibbity bobbity boo.’ Or. ‘War is peace, freedom is slavery…etc.’

Leaving such, reality distorting statistical manipulation aside, there are many other diseases that you can die of including, let me think: breast cancer, colorectal cancer, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, autism, asthma, type 1 diabetes …etc.

If you protect against one thing, but in so doing, increase the risk of many others, you have just done significantly far more harm than good. To look at just one of the other potential forms of death that sun exposure could protect us from – colorectal cancer:

Gorham et al examined five studies on association of serum 25(OH)D (vitamin D) and colorectal cancer risk. A meta-analysis indicated a 104% higher risk associated with serum 25(OH)D <30 nmol/L compared to >82 nmol/. 3

- Malignant melanoma kills around two thousand five hundred people a year in the UK.

- Colorectal cancer kills around seventeen thousand people a year in the UK.

This ratio of around one, to eight, is pretty much the same in most other countries. So, dear reader, which of these forms of cancer should you be more interested in preventing?

Simple sum here – assuming ‘best/worst case’ scenarios in either direction:

- Malignant melanoma kills 2,500 per year. If avoiding the sun prevented this completely, we could save 2,500 lives.

- Colorectal cancer (CRC) kills 17,500 per year. If avoiding the sun increases the risk of death by 104%, we have caused 18,200 excess deaths.

Would the figures change as dramatically as this? Almost certainly not, nowhere near. My figures represent a thought experiment. However, here is what Google AI informs me about colo-rectal cancer:

‘There’s a significant and concerning rise in bowel cancer among young people in the UK, with rates in those under 50 increasing by around 50% since the mid-1990s.’ This is a trend seen around the world. As for Australia. ‘Yes, there’s a significant and concerning rise in bowel cancer among young Australians (under 50), with Australia having the world’s highest rates for this age group.’

Highest rates of CRC in the country where sun exposure is dreaded more than any other? Has anyone even suggested sun exposure, or the lack of it, may play a role? Nope, complete and utter silence on the matter. Can’t even be mentioned, it seems.

Moving on from bowel cancer, I feel the need to make the point that the most significant impact on dying, if you avoid the sun, appears to be on heart disease. This kills 175,000 people each year in the UK. Reduce that number by one and half per-cent you will have saved as many lives as can possibly die of malignant melanoma. Logic, where art though?

How can the concern about one disease trump all others so completely? Primarily, I believe, it is because dermatologists have managed to gain dominance in the world of sun exposure, with their very simple message. ‘Sunshine damages the skin and causes skin cancer, and so it must be avoided at all costs.’

Focussing on one thing to the exclusion of all else is a cognitive bias known as the focusing effect/illusion. For a dermatologist malignant melanoma is their number one issue/disease. Any suggestion that the sun may be good for us is ruthlessly stomped on. ‘Your ideas are killing people’ is the normal line of attack – believe me, I know this line of attack well.

And the public have been convinced. And the medical profession has become convinced – as has almost everyone in the entire world. Try telling the average person that sun exposure is extremely good for you, and they look at you as if you were mad, bad, and dangerous to know.

I don’t find this type of concrete, straight line, focussed thinking, strange anymore. Over the years I have stumbled across many areas of medicine where bad ideas have taken hold, and simply cannot be shifted. Indeed, they only seem to strengthen under attack.

I have been banging on about saturated fat for decades. The evidence that saturated fat is bad for you has always been weak, to non-existent, to totally contradictory. Yet, and yet, the idea continues to hold sway over most of the population. With little sign that it is losing its grip. One day, perhaps, I can dream.

Salt … if there is any good evidence on this, it suggests that salt is good for you. But the idea that salt is harmful is also immovable, and unchanging. Evidence that it reduces life expectancy, there is none. And I mean … none.

So, what does it take to change thinking. If I knew how to sweep aside wrong ideas, I would have managed it by now. Disruptive science? Disruptive evidence? It is actually out there, but no-one pays much attention to it. In general, it is first mocked, then attacked, then dismissed.

Somehow, somehow, we have to think in different ways. I was going to say better ways, but that sounds a little on the elitest side. ‘I think better than you.’ When it comes to sunshine, it really isn’t difficult to change the thinking, is it?

I cannot find any evidence, anywhere, that it is anything other than extremely good for us. Ergo, hiding away from the sun is bad for us. One of the worst things we can possibly do, and it is also one of the easiest, and most pleasurable things, to rectify. Go out and sunbathe. [Yes, of course, I have to add, but do not burn. As if everyone in the world is a complete idiot that cannot understand even the simplest idea.]

But, but, but …instead, we have all been – made to be – terrified of skin cancer. A condition which kills very few people each year. It seems impossible to move the thinking beyond this barrier … bonkers. And very harmful indeed.

In my next blog on disruptive science, I will look again at sunshine, from a different perspective, including the question. Does it actually increase the risk of malignant melanoma?

1: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26992108/

2: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/14/5014 3: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0749379706004983